Examination of how DSGE models address the limitations of Real Business Cycle analysis.

Arina Kenbayeva / May 10, 2023

This paper explores how Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models improve upon the limitations of Real Business Cycle (RBC) analysis in explaining macroeconomic fluctuations. It discusses the core assumptions of RBC models, including the emphasis on technological shocks, flexible prices, and perfect markets, and critiques their oversimplification of economic dynamics. The paper then highlights how DSGE models incorporate elements like sticky prices, financial frictions, and involuntary unemployment to provide a more realistic representation of business cycles. Despite these improvements, DSGE models still face limitations, requiring further refinement for effective economic policy application.

I. INTRODUCTION

The world economy is constantly changing due to various factors such as technological advancements, political decisions, market trends, natural disasters, and even pandemics. These fluctuations can have positive or negative consequences for individuals, businesses, and entire economies. Given the complexity and unpredictability of the economy, there is a necessity for models that can predict and explain fluctuations. Economic models seek to better understand how various factors interact and to identify causal relationships between different variables. These models can be used to create scenarios and help policymakers make informed decisions.

Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models are prominent approaches used to understand the business cycle fluctuations in the economy. The very first DSGE models—called real business cycle models – posit that macroeconomic fluctuations in the economy can be largely explained by technological shocks and changes in productivity. However, this approach has been criticized for oversimplifying the complexity of the economy and its interactions. On the other hand, later DSGE models aim to address some of the limitations of the RBC approach by incorporating, for example, effects of public finance elements, a foreign sector, and monetary factors. This essay aims to examine how DSGE models improve upon the limitations of the RBC analysis and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the business cycle fluctuations. In the first part of the essay, DSGE models with their special case, RBC model, will be explained. Then, the DSGE model will be presented with the comparison with the RBC model to answer the question of the Essay.

Ⅱ. DSGE Models and its special case, RBC model, explanation

Dynamic, stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models sit at the frontier of the analysis of macroeconomic fluctuations. The models incorporate multiple shocks to the economy (hence they are stochastic), they feature multiple markets with prices that adjust endogenously to clear the markets (hence they are general equilibrium), and they explain how the economy evolves over time in response to shocks (hence they are dynamic). The first DSGE models were real business cycle models. These approaches applied growth models, like the Solow model, to the study of macroeconomic fluctuations. A key finding of these early models was that total factor productivity shocks could lead to fluctuations that resemble business cycles in many ways; for example, by causing wages and employment to decline during a recession. A positive TFP shock would result in an economic surge, while a negative TFP shock would lead to a decline in GDP . The models were named RBC models because these shocks were real and the resulting output displayed fluctuations comparable to those observed during a business cycle. Real business cycle models either completely reject or play down the role of aggregate demand in influencing the economic cycle. Real business cycle models suggest that government intervention to influence demand in the economy is generally counterproductive and the optimal policy is to concentrate on supply-side reforms which help the economy to be more efficient and flexible.

Ⅲ. Comparisons of the models

While RBC analysis has been extensively researched and widely accepted, it still faces several limitations.

a. Shocks

One limitation of RBC analysis is that it ignores crucial factors that influence the economy. It states that macroeconomic fluctuations in the economy can be largely explained just by technological/supply side shocks and changes in productivity, when in reality it is not true.

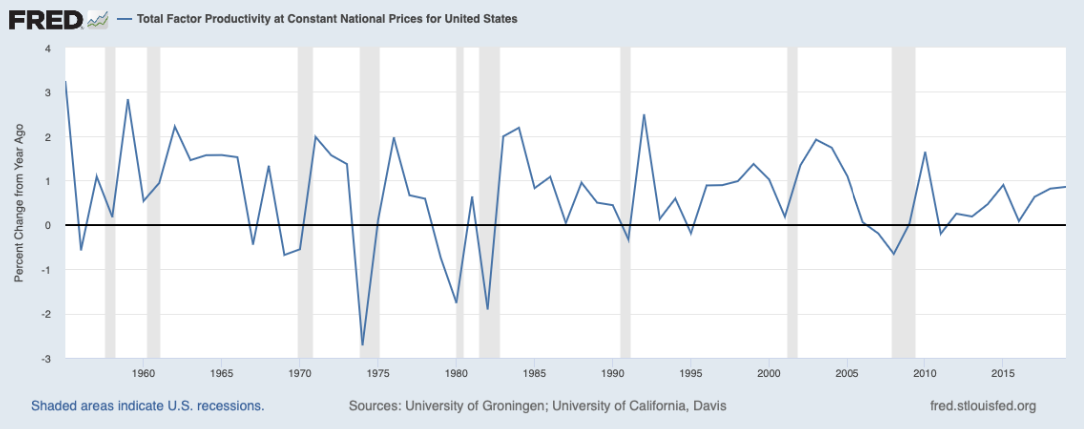

For better understanding it will be efficient to look at Figure 1.

Figure 1. Total Factor Productivity at Constant National Price for United States

Figure 1. Total Factor Productivity at Constant National Price for United States

In some recessions like the 1960-1961 or early 2000s recessions, there is no negative TFP shock associated with the recession.

DSGE later models address this limitation by including many other possible shocks such as shocks to government purchases, “news” of future changes in the economy, financial frictions, and shocks to consumption and monetary shock. New Keynesian model-one of the DSGE later models-uses the last noted shock.

b. Prices and Wages

An important consideration in all models of economic fluctuations is whether or not prices are flexible or sticky. Models with fully flexible wages and prices often deliver different implications for the effect of particular shocks. Real business cycle models emphasize models with perfectly flexible wages and prices. It suggests that prices and wages are elastic, which means that when there is a shock, adjustments are going to be immediate, and there is no place for market failures. For example, a fall in aggregate demand for labor would cause a fall in wages. This decline in wages would ensure that full employment was maintained and markets ‘clear’.

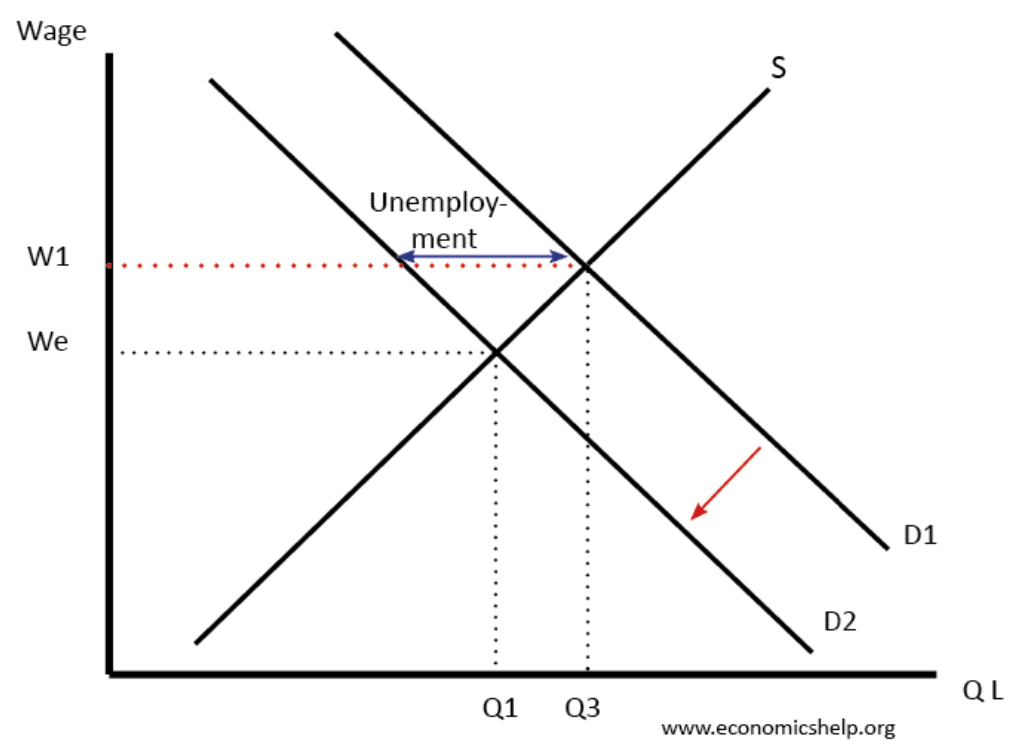

Figure 2. Flexibility of prices and wages.

Figure 2. Flexibility of prices and wages.

However, in the real world, wages and prices are often inflexible. T o solve this limitation of RBC model DSGE models emphasize nominal rigidities like sticky wages and sticky prices. They are used In order for monetary policy to have real effects on the economy.

c. Adjustment costs.

In the RBC model, the effect of a shock is largest immediately after it hits. In the data, however, this is often not the case. One example of this is inherent in Milton Friedman’s comment that monetary policy has its peak effect only after “long and variable lags. ” DSGE models typically include adjustment costs to capital: it is particularly expensive to change the capital stock by a large amount. This has the effect of “slowing down” the dynamic response of macroeconomic variables to shocks, often leading the peak effect of the shock to occur several periods after the shock itself.

d. Complete/Incomplete markets

The RBC model is based on complete markets. That is, any trade between people—even if they are separated by time or geography or circumstances—is permitted. However, adverse selection and moral hazard might exist, for example, leading certain markets to be absent. For example, it may not be possible for me to perfectly insure my consumption against the possibility that I lose my job next year. DSGE models address this issue by using incomplete markets. With incomplete markets, shocks may have larger effects on the economy, and these shocks may be more costly. For example, unemployment may be concentrated on a subset of the labor force, and those who are unemployed may experience a disproportionate decline in consumption.

e. Unemployment

A technological shock can cause resources to move from one sector to another. But, it can take time for labour to move between different jobs. Therefore, there can be temporary structural unemployment. Another cause of unemployment in a real business cycle is due to the consequences of agents changing their decision to supply labour. Under some circumstances of technological change/change in trade unions power – workers may choose voluntary unemployment rather than supplying labour. Unemployment reflects changes in the amount people want to work. Paul Krugman argued that this assumption would mean that 25% unemployment at the height of the Great Depression (1933) would be the result of a mass decision to take a long vacation, which is not true. DSGE models cover this by using the concept of involuntary unemployment. That is, there are people who would like to work at the prevailing wage but who are unable to find jobs. This is a direct consequence of the wage being “stuck” at a level that is too high to clear the labor market. This mechanism is one of the key ways that DSGE models incorporate unemployment."

f. Market Structure

The Real Business Cycle model assumes perfect competition in the market, where all firms are price-takers and there is no market power exerted by anyone. However, in reality, there is always some degree of market power, making the assumption of perfect competition unrealistic. T o address this limitation of the RBC model, the DSGE model incorporates a form of market power through monopolistic competition. In monopolistic competition, firms have some degree of market power to set prices, leading to imperfect competition. This model allows for a better understanding of the real-world economy, where market power exists to some extent.

Ⅳ. Limitations of DSGE models

Despite the fact that models address limitations of its first version, DSGE models still have their own limitations: First, they still need to incorporate relevant transmission mechanisms or sectors of the economy; second, issues remain on how to empirically validate them; and finally, challenges remain on how to effectively communicate their features and implications to policy makers and to the public.

Ⅴ. Conclusion

In conclusion, the world economy is constantly changing and complex, due to various factors that can result in positive or negative consequences. Given this unpredictability, models that can predict and explain fluctuations are necessary for policymakers to make informed decisions. The RBC model was the first DSGE model used to study macroeconomic fluctuations, with its focus on real shocks and changes in productivity. However, it has been criticized for oversimplifying the complexity of the economy and its interactions. Later DSGE models addressed some of these limitations by incorporating effects of sticky prices and wages, other shocks beside TFP , adjustments costs, etc. Despite these improvements, DSGE models, including the latest ones, still have their own limitations. Therefore, continual research is needed to improve the models and provide a comprehensive understanding of the business cycle fluctuations, ultimately helping policymakers to make better decisions.