Women that played a crucial role in the oil history

Arina Kenbayeva / May 12, 2024

This essay discusses two women journalists, Ida Tarbell and Wanda Jablonski, who defied male-dominated norms in journalism and the oil industry, reshaping history through fearless investigation and diplomacy. Tarbell’s exposé dismantled Rockefeller’s Standard Oil monopoly, while Jablonski’s behind-the-scenes diplomacy laid the groundwork for OPEC—proving women’s pivotal yet often overlooked roles in global oil dynamics. Their legacies highlight perseverance and the power of challenging entrenched power structures.

INTRODUCTION

It is no secret that the oil industry is associated with such names as Rockefeller, Rothschild, and Nobel. They filled all the pages of oil history and established their dominance in the oil market. It would seem that there is no place for women in the oil business, but two female journalists proved the opposite, changing the course of oil history with their fearlessness and persistence.

The first is Ida Minerva Tarbel. She was born on November 5, 1857, in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania is an “oil” state, and so Ida's father, Franklin Sumner Tarbell, a carpenter by trade, built wooden tanks for oil storage.

Figure 1. The first oil rigs in America

Figure 1. The first oil rigs in America

In 1860, Franklin moved the family to Titusville, one of the “oil capitals'' of America. Here Ida graduated from high school, becoming the top student in her class, after which she started a biology major at Allegheny College. After college, Tarbell spent two years working as a teacher in Ohio but then switched to journalism and literary documentary.

The America of Ida Tarbell's youth was very different from modern America. Boys and girls went to school separately, and most of Ida's classmates dreamed only of marrying well. Ida's dream was to build a successful career. So her education had to continue in freer France, where institutions did not have such a gender bias.

Figure 2. Ida Tarbell

Figure 2. Ida Tarbell

During her studies in France, Ida collected material for books devoted to famous Frenchmen. Thus, in 1896, The Short Life of Napoleon Bonaparte and Madame Rolland were published, which became very popular.

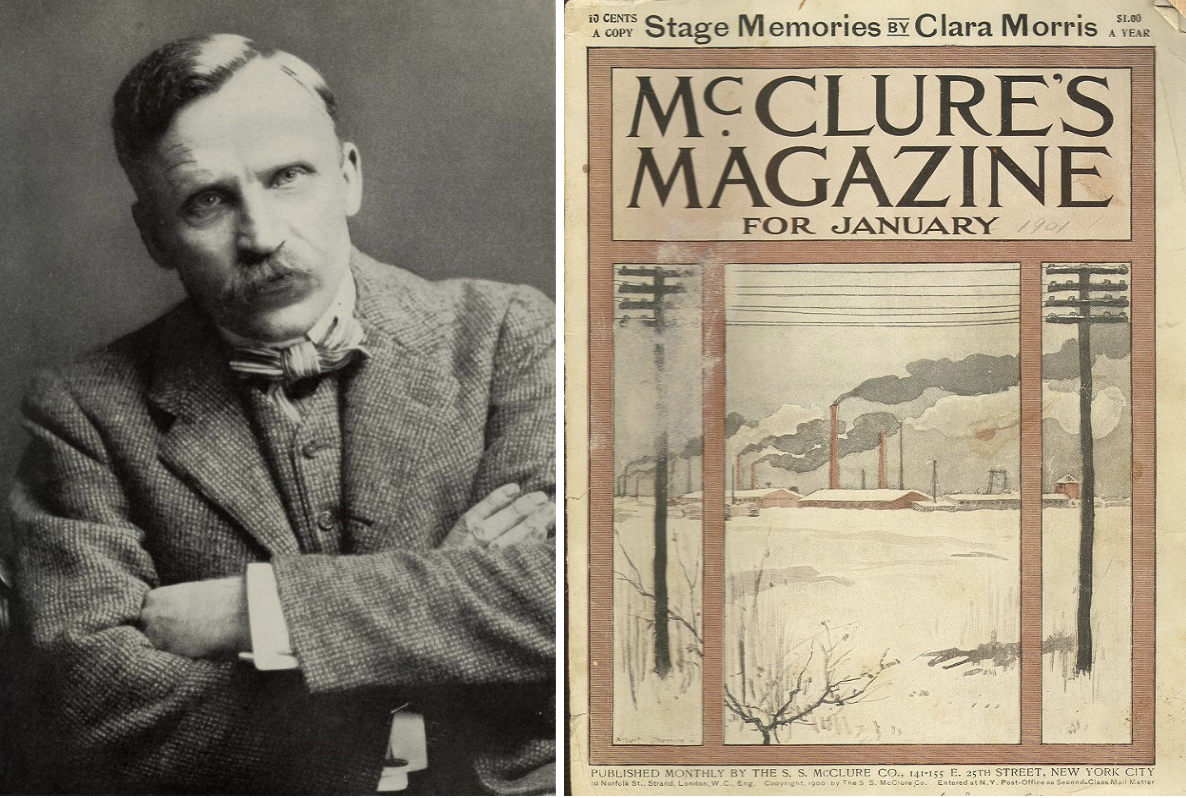

Ida's success attracted publisher Samuel McClure, owner of the increasingly famous McClure's Magazine, and Tarbell soon became one of the magazine's key contributors.

Figure 3. Samuel McClure and McClure’s Magazine

Figure 3. Samuel McClure and McClure’s Magazine

McClure's Magazine was famous for its investigative journalism, and people who wrote there were nicknamed “muckrakers” by US President Theodore Roosevelt.

The factor that determined the direction of Tarbell's work was her “oil” origin, and the fact that Ida's father went bankrupt amid the monopolization of oil production in the hands of Rockefeller's Standard Oil.

In the end, the maximalist Ida decided not to trifle, choosing as her target Standard Oil and its owner John Davison Rockefeller, the richest man on the planet, the owner of an oil empire that includes 400 enterprises, 90 thousand miles of pipelines, 10 thousand railroad tank cars, 60 ocean tankers, and 150 river steamers.

The main source of information for Ida’s investigation was Standard Oil’s Vice President Henry Rogers, who oversaw gas production and pipeline transportation for the company. The acquaintance of Tarbell and Rogers was organized by Mark Twain, a close friend of the high-ranking oilman. (Rogers and Twain met in 1893 through mutual acquaintances. Their friendship was not only personal but also professional, as Rogers became one of Twain's financial advisors and played a significant role in managing Twain's investments and business affairs.) Tarbell and Rogers met in early 1902 at the offices of Standard Oil in New York. It turned out that Rogers and Tarbell were the closest countrymen and neighbors. Rogers even remembered Frank Tarbell as well.

Figure 4. Henry Huttleston Rogers

Figure 4. Henry Huttleston Rogers

Tarbell began meeting and interviewing Rogers regularly. Moreover, Ida was given a workstation in the company's office and given access to confidential documents. In addition, Rogers provided Tarbell with constant and comprehensive assistance - arranging interviews with company managers, and providing materials, explanations, and comments, including on sensitive topics such as government relations, campaign financing, and legislative initiatives.

Thus, thanks to Rogers, Tarbell has collected a huge and in many ways unique material. The question of why Rogers so actively helped Ida is still a mystery.

Perhaps it was revenge on Rockefeller, with whom he may have been in a quarrel at the time. However, he gave a pragmatic explanation: the book will still be written, so it is necessary to try to make sure that the company's case was presented “as it should be”. Nevertheless, when the first articles leading up to the book's release began to appear, Rogers was furious. He died in 1909, before the breakup of the company, but his legacy remained intertwined with the rise and fall of one of the most influential corporations in American history.

Tarbell had accomplished one of the primary goals of the nation's emerging political transformation at the time: controlling and regulating big business. Publications about the Rockefeller firm's flirtations with legislation, tax refund practices, and campaign financing - appeared regularly in the pages of McClure's for two years, and then were compiled into a book. The book was written in simple and accessible language, contained 64 appendices (copies of confidential documents), and was a complete description of the development of the company from its inception to the beginning of the twentieth century.

Figure 5. The History of the Standard Oil Company

Figure 5. The History of the Standard Oil Company

The appearance of this book was a sensational event since for the first time Ida Tarbell explained to her fellow citizens how this world works - that everything is decided not in Congress, not in the White House, but in the offices of companies such as “Standard Oil”. The book became a major bestseller in America and this status it still has today, occupying the 5th place in the list of 100 best works of American documentaries.

In addition to the fact that Tarbell was not afraid to write about the country's first oil company, a powerful giant, Ida Tarbell was also not afraid to write about John Rockefeller himself. “Mr. Rockefeller has been systematically playing with speckled cards. And it is very doubtful that since 1872, in races with competitors, he has even once started fairly”, she later wrote. She also wrote that “our lives are on all sides noticeably poorer, uglier, meaner, because of the influence he exerts.”

How Rockefeller's security and huge legal staff could have missed a small journalist asking uncomfortable questions of their workers for several years is completely incomprehensible. Apparently, no one took her seriously; journalism at that time was practiced mostly by men. And as we can see, they made a big mistake, deciding that it was not worth paying attention to the curious lady from the magazine.

Since the dirt on Rockefeller and his company went to Tarbell "by gravity", Ida continued to attack Standard Oil and its odious chief. In doing so, Tarbell went beyond condemning Standard Oil - she offered a thoughtful program to combat its monopolistic position in the market. Ida's publications convinced that the time had come to apply effective anti-monopoly measures to the oil monster.

Tarbell's ideas fell on fertile ground as she found support in the person of President Theodore Roosevelt and members of his team. Ironically, Roosevelt's presidential campaign was financed by Rockefeller.

In November 1906, the Roosevelt administration's lawsuit against Standard Oil began in a federal district court in St. Louis. The charge was a conspiracy to restrain free trade, the legal basis being the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. The state prosecution was led by Frank Kellogg, an experienced lawyer and specialist in corporate law, who 19 years later became U.S. Secretary of State.

The whole world followed the trial against Standard Oil. The trial took place over two years. During this period, more than 400 witnesses testified, and almost 1.4 thousand documents were presented to the court. The full record of the case took up 14.5 thousand pages, combined into 21 volumes. Finally, in 1909, the federal court ruled in favor of the government and ordered the liquidation of Standard Oil. Roosevelt, who by then had already resigned his presidential powers, greeted the news with great joy: “This court decision is one of the most remarkable triumphs of decency.”

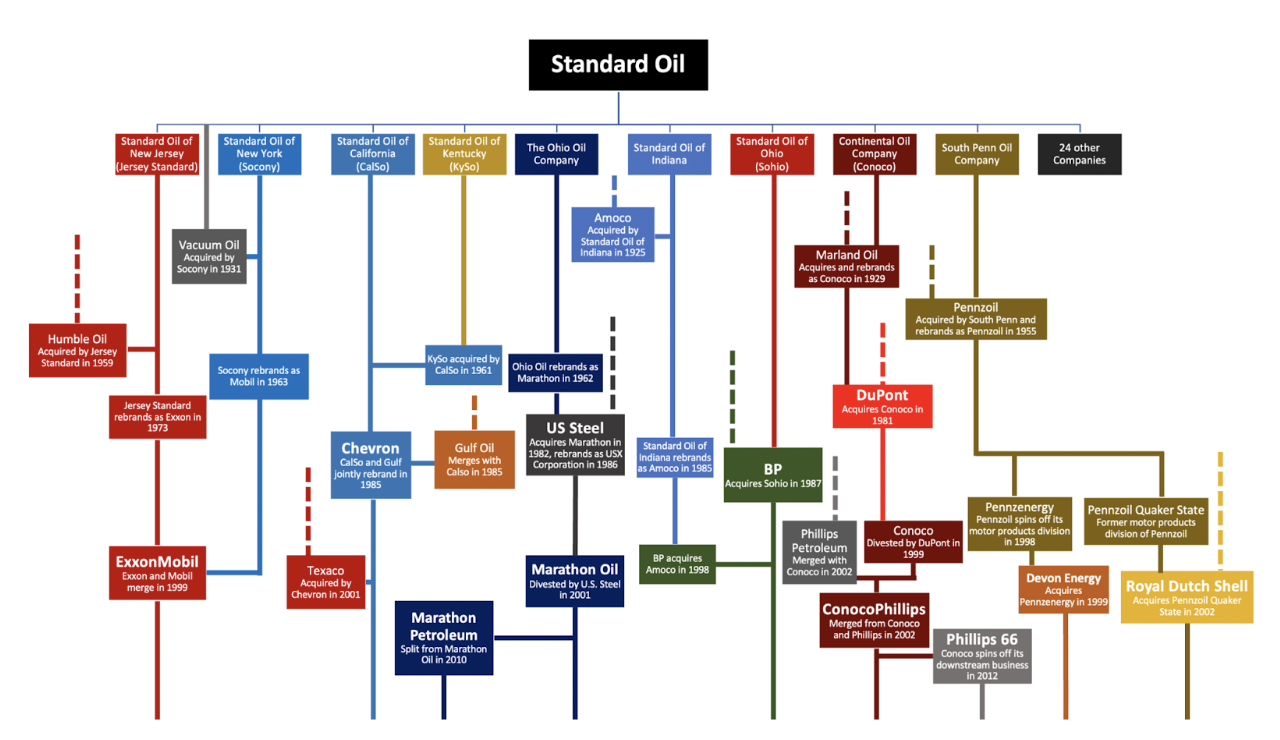

Standard Oil, however, continued to fight. The company appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, after which the case was heard for two more years. The final decision was made in May 1911 - Standard Oil was to be liquidated, and its oil business divided into 34 independent companies, the biggest two of the companies were Standard Oil of New Jersey and Standard Oil of New York (ExxonMobil later).

Figure 6. Abbreviated chart of some of Standard Oil's successors

Figure 6. Abbreviated chart of some of Standard Oil's successors

The empire fell, and the oil industry in America, and indeed the world, took on a whole new, competitive face.

The American public applauded the courageous journalist and the court decision. Everyone was happy that they had nailed the hated monopolists. Investigative journalism began to gain popularity - everyone tried to publish an article, not caring whether it was true or false, the main thing was to turn it into a scandal.

Ida's father, forty years ago ruined by Rockefeller, had lived to see this day. Frank Tarbell was avenged.

And Ida lived another 33 years, wrote many good books and articles, becoming in her lifetime a legend and icon of American journalism. Her views did not change, advocating “capitalism with a human face”. Socialist ideas of redistribution of national wealth seemed unrealistic to her, and socialism itself - “imported panacea”. Tarbell did not doubt that reforms could “modify and correct” capitalism.

It is also important that Tarbell was a strong supporter of women's equality and wrote a famous book on this subject in 1915, “Women's Paths”. Alas, Ida never married. She lived in a modest house in the town of Easton, Connecticut. Now this house and estate - a popular attraction, a museum site. Tarbell managed to write a detailed book about her own life - “All in a Day's Work: An Autobiography” in 1939. She died of complicated pneumonia on January 6, 1944, at the age of 87.

Figure 7. Ida Tarbell’s house

Figure 7. Ida Tarbell’s house

Ida Tarbell fought the U.S. oil monopoly, while another prominent journalist, on the contrary, helped to negotiate an agreement to create the international OPEC cartel. Wanda Jablonski was considered the most influential oil journalist of her time.

Elegant, beautiful, intelligent, and determined Wanda Jablonski was a worthy daughter of her parents. Wanda's mother, Maria Kemeri, was born into the family of a prominent Slovak politician and senator, Karol Kemeri. By the age of 22, she had two higher education degrees and planned to get a master's degree in biological sciences at the Budapest University of Natural Sciences. It was there that she met her future husband, the eminent botanical scientist Eugene Jablonski.

Figure 8. Wanda Jablonski’s father

Figure 8. Wanda Jablonski’s father

Eugene was prophesied to have a brilliant scientific future. In 1914, he was a graduate of the University of Berlin, and a doctoral student at the University of Budapest, working on a topic at the intersection of botany and geology. But the dreams and plans of the scientist were thwarted by World War I - Jablonski was mobilized in the army and sent to the Eastern Front. A year later, Eugene, who fought in the Austro-Hungarian army, was taken prisoner in Ukraine, where he spent more than three years. Only in 1918 was he able to escape from captivity and return to Budapest, to his fiancée. By that time they had been engaged for nine years and were soon married.

What followed was a happy marriage, the birth of their daughter Wanda in August 1920, and desperate poverty in post-war Poland. Tired of poverty, Maria asked her husband to stop scientific research and take up practical and much better-paid geology. Moreover, there was an acute shortage of qualified geologists in the country. So Eugene came to work for Standard Oil of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil). This was followed by a dramatic change in the fortunes of the Jablonski family - Eugene was transferred to work in America.

Yablonski's duties included searching for oil in various regions of the world, and his family had to lead a nomadic lifestyle. Thus, before entering the university, Wanda Jablonski studied in schools in 8 countries - the USA, New Zealand, Egypt, England, Morocco, Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia. Thanks to her father, Wanda met prominent geologists, such as Max Steinecke, who discovered the oil fields of Saudi Arabia.

In 1939, Wanda enrolled at Oxford University, but her studies were interrupted by World War II. The Jablonskys moved to the United States. Wanda sent letters to the leading American universities - Harvard and Yale, but was rejected - these educational institutions were practically closed to women at that time. Then Wanda entered the biology department of Cornell University. A year later Wanda transferred to the Faculty of International Relations and Law, in 1942 she successfully completed her bachelor's degree, and in 1943 - a master's degree in International Journalism at Columbia University.

Filled with the brightest hopes, Wanda began to look for work, but, alas, everywhere met with rejection. One day Wanda saw a newspaper ad: “The New York Journal of Commerce needs a courier”. So the master of international journalism became an editorial courier. In this hectic position, Wanda worked for more than a year. Having penetrated the specifics of American business journalism, Wanda wrote a large article about the U.S. coal industry. The article was characterized by in-depth analysis and a distinctly individual style and rightfully became a front-page article.

Gradually, Jablonski's articles gained widespread popularity. Given that information prepared by women was generally viewed negatively in the American business world, the editor-in-chief advised Wanda to sign her article W. Jablonski, without deciphering the name. After some time, Wanda suggested to the editor that she publish a magazine supplement devoted to the oil industry, Petroleum Week.

The proposal was accepted, and Wanda, using her father's knowledge and contacts, began to prepare analytical materials regularly, which brought her great popularity among the world's oil elite. Jablonski became a real “shark” of industry journalism and analytics. Within a short time, Wanda established friendly and trusting relations with the heads of all major oil companies in the world and interviewed leaders of oil exporting countries. Interestingly, she interviewed the King of Saudi Arabia in his harem, disguised in a hijab. “Guess where I spent last night? - quipped Wanda. - In the harem of the king of Saudi Arabia! Before you jump to conclusions, I hasten to add that I was there... drinking tea (with rose water).”

This is how Wanda Jablonski became one of the most influential columnists, experts, and analysts in the global strictly male oil and gas industry.

Figure 9. Wanda Jablonski and the First Minister of Oil and Mineral Resources of Saudi Arabia, Abdullah ibn Hamoud Tariki

Figure 9. Wanda Jablonski and the First Minister of Oil and Mineral Resources of Saudi Arabia, Abdullah ibn Hamoud Tariki

In the late 50s of the last century, there was a confrontation between Western oil companies and third-world exporting countries. At that time, the oil industry was controlled by an Anglo-American cartel nicknamed the “Seven Sisters”. At the peak of their development, they concentrated in their hands almost 90% of the world's oil reserves. The monopoly position in the sales market allowed the “sisters” to ruthlessly pressurize their counterparts from developing countries, forcing them time after time to lower their selling prices.

In an attempt to increase profits, governments increased production, but market constraints led to an oversupply of oil. In such circumstances, exporters fought their competitors with discounts. In some cases, they may have helped an individual country, but they hurt the overall market. Around the same time, the Soviet Union entered the world market as a supplier. This meant that the excess of oil on the market only increased. In addition, the USSR was actively using price cutting - and Western companies were forced to do the same, as they did not want to lose margins due to competition with the communists. In 1959, oil companies unilaterally cut the official price by 10%, reducing the income of exporters.

The producing countries were outraged. Juan Pablo Perez Alfonso, Venezuela's Minister of Fuel Industry, and Abdullah ibn-Hamoud Tariki, head of Saudi Arabia's Directorate of Petroleum and Mining Affairs (later the first Saudi oil minister), were most outraged. These men might not have known of each other's solidarity if it had not been for Wanda Jablonski. In April 1959, the Arab Petroleum Congress opened in Cairo. Jablonski traveled there to introduce Tariki and Peres.

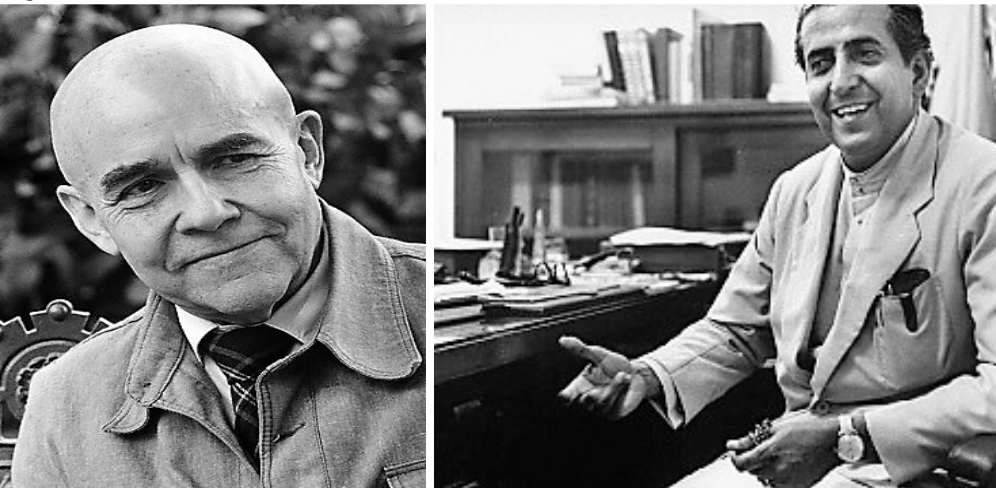

Figure 10. Juan Pablo Perez Alfonso and Abdullah ibn-Hamoud Tariki

Figure 10. Juan Pablo Perez Alfonso and Abdullah ibn-Hamoud Tariki

The meeting of the influential statesmen took place in strict secrecy in Wanda's hotel room. At the meeting, Tariki and Peres agreed to hold talks with representatives of Iran, Kuwait, and Iraq. A day later, a “Gentleman’s Agreement” was reached, providing for the establishment of an Oil Advisory Committee, changes in pricing policy, and the formation of national oil companies. Thus, in Cairo's Hilton Hotel, the premises of the future OPEC, created a year later, in September 1960, at the Baghdad forum with the participation of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela, were defined.

As for Wanda Jablonski, another year later, in 1961, she organized her own business publication in New York, Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, where she became sole owner, publisher, and editor-in-chief. Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, which Wanda ran for more than a quarter of a century, not only became the “bible of the oil industry”, but also made Jablonski a multi-millionaire.

Wanda Jablonski died in January 1992 at the age of 70, remaining the most influential figure in the global oil and gas business until the end of her life.

In conclusion, the stories of Ida Tarbell and Wanda Jablonski serve as compelling narratives of courage, perseverance, and groundbreaking achievements in the male-dominated world of journalism and the oil industry. They have shown that it is necessary to confront societal barriers and overcome entrenched biases and prejudices. By fearlessly challenging the status quo, these journalists have shown that even one person can have a significant impact and change the trajectory of history.

References

-

Tarbell, I. M. (1939). All in the day’s work: an autobiography. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/63754/pg63754-images.html

-

Yergin, D. (1991). The prize: the epic quest for oil, money, and power. The New England Quarterly, 64(3), 520. https://doi.org/10.2307/366363

-

Wikipedia contributors. (2024, April 2). Ida Tarbell. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ida_Tarbell

-

Nuñez, C. B. (2009). Queen of the Oil Club. The intrepid Wanda Jablonski and the power of information. Journal of World Energy Law and Business, 2(2), 168–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/jwelb/jwp007

-

Mark Twain’s Correspondence with Henry Huttleston Rogers, 1893-1909. (n.d.). University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520014671/mark-twains-correspondence-with-henry-huttleston-rogers-1893-1909